Children’s Corner

EVENTS LEADING TO THE MORANT BAY REBELLION OF 1865

Emancipation on August 1, 1838 was followed by years of hardship for the ex-slaves and financial struggles for the plantation owners due mainly to poor estate management. Also, the decline in the price of sugar made production unprofitable, so some planters sold their estates and many who worked on the sugar plantations lost their jobs.

In 1864, Edward Eyre was made Governor of Jamaica. He was unsympathetic towards the poor who were constantly being arrested for petty offences, and planters and ex-slave owners were cruel to them.

HOW NATIONAL HEROES GEORGE WILLIAM GORDON AND PAUL BOGLE PLAYED THEIR ROLES IN THE REBELLION

George William Gordon was a Justice of the Peace in St. Thomas who showed interest in and sympathy for the poor. He was educated and a very rich businessman. He realised that the people needed justice in the courts and doctors to care for them, so he reported the matter to Governor Eyre who did nothing to resolve the plight of the poor but rather removed Gordon as Justice of the Peace. However, Gordon still maintained his goal to help the poor, and he ran in an election and won a seat in the House of Assembly.

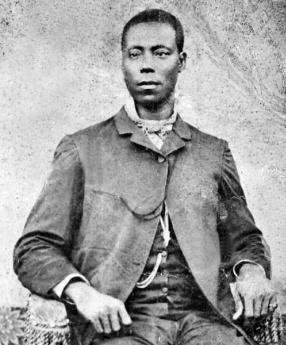

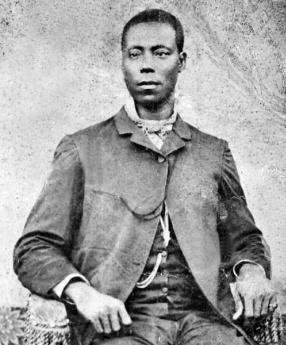

Paul Bogle, a farmer and deacon in the Native Baptist Church, was also concerned about the hardships experienced by the people. He, along with sympathisers of the Native Baptist movement, supported Gordon in his campaign to win his seat in the Assembly.

As leader of a group in Stony Gut, St. Thomas, Bogle wanted to air the grievances of the poor to Governor Eyre, but was refused an airing. He decided to take matters in hand and began to train persons for combat, and led a riot on October 11, 1865 that resulted in the Custos of the parish being killed and the Morant Bay Courthouse being burnt to the ground.

Governor Eyre sent government troops to hunt down the poorly armed rebels and the Maroons captured Bogle and brought him back to Morant Bay for trial. The troops met with no organised resistance, but regardless, they killed Blacks indiscriminately, most of whom had not been involved in the riot or rebellion. In the end, 439 Black Jamaicans were killed directly by soldiers, and 354 more (including Bogle and Gordon) were arrested and later executed, some without proper trials.

George William Gordon and Paul Bogle gave their lives for the betterment of the poor in Jamaica. In 1977 they were awarded the title of National Hero.

CHILDREN CORNER ACTIVITIES

Click to access each activity. Print and Enjoy!

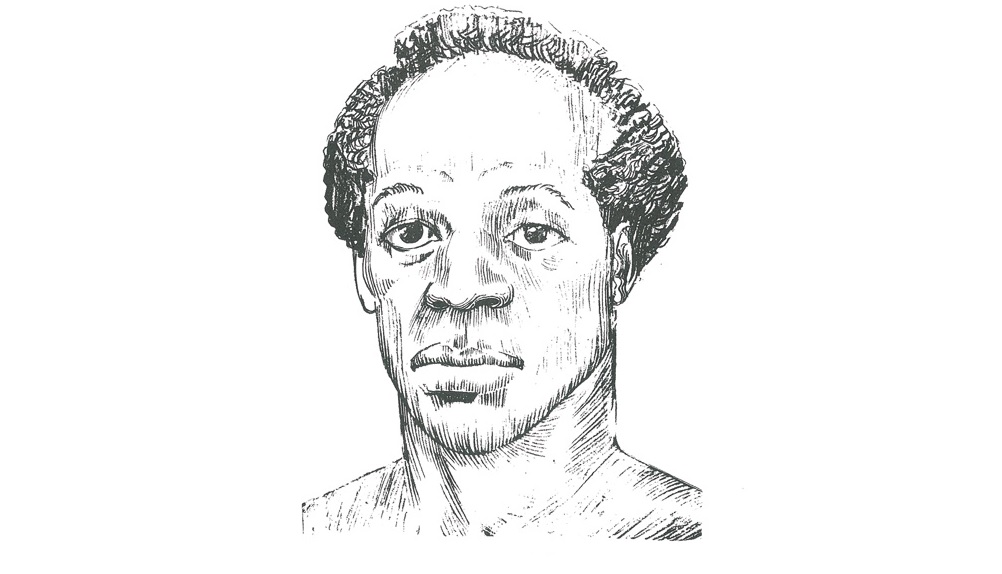

THE LIFE AND WORK OF NATIONAL HERO PAUL BOGLE

Paul Bogle was born in Stony Gut, St. Thomas, a few miles north of Morant Bay. He was a deacon in the Native Baptist Church in Stony Gut, St. Thomas. He was well respected in his district, had great influence among his peers, and was considered to be a natural leader. He was an energetic man with a dominant personality and, although he had very little formal education, he was a successful small farmer. His faith in God led him to believe that, in some way, he was an instrument of God to be used for the betterment of the people. Bogle was among 106 inhabitants in the parish of St. Thomas who had the right to vote. He was the political agent for George William Gordon, to whom he had religious ties. He was also the leader of the movement for passive resistance to oppression and injustice in the parish of St. Thomas. When this approach failed, he later teamed with his brother, Moses, in leading an active resistance movement in St. Thomas that culminated in the Morant Bay Rebellion of 1865.

Bogle’s Involvement in the Morant Bay Rebellion

The year 1865 was one of severe trials for the majority of the people of Jamaica as wages were extremely low and peasant farmers were unable to procure land for cultivation. Bogle was driven by the conditions of the majority of the people to protest against the poverty and injustice in the society. On the morning of August 12, 1865, Bogle walked 45 miles from Stony Gut to Spanish Town to present the grievances of the people of Morant Bay to the Governor, Edward Eyre, but was denied an audience.

Bogle started to hold secret meetings in the hills and drilled his followers to form a small army. Early in October 1865, two of Bogle’s followers were to be tried in Morant Bay. On October 7, Bogle and his group marched into Morant Bay and arrived at the courthouse where the trial of a peasant was in progress. The proceedings were disrupted by angry members of the crowd in the court room. The police tried to arrest a man who appeared to be the main offender and a fight broke out between them and Bogle’s men.

Three days later, a squad of policemen went to Stony Gut to arrest Bogle but were overpowered by some of Bogle’s men. Bogle and his committee sent a letter of appeal to the Governor, indicating that the warrant for his arrest was unlawful.

On their return to Morant Bay, the police reported the incident to the Custos who requested military aid from the Governor. The Custos decided to hold the regular meeting of the Vestry on October 11 and called out the militia.

On the day of the vestry meeting, Bogle started for Morant Bay with his followers. Some members of Bogle’s army broke into a police station and stole weapons, and then the crowd met outside the courthouse in Morant Bay.

There was an angry interchange between Bogle’s men and the militia. The Custos read the Riot Act and ordered the militia to fire on the crowd after an officer was injured in a stone-throwing incident.

The crowd killed members of the militia and forced others into the courthouse. A building behind the courthouse was set on fire and, as the flames spread to the main building, many people were killed including the Custos.

Bogle marched some of his men out of Morant Bay, leaving a garrison behind in control of the town. Martial Law was proclaimed and, by October 16, hundreds of people in St. Thomas were arrested, but Bogle could not be found. Bogle was caught by a party of Maroons and brought to Morant Bay for trial. He was hanged on October 24, 1865.

Bogle marched some of his men out of Morant Bay, leaving a garrison behind in control of the town. Martial Law was proclaimed and, by October 16, hundreds of people in St. Thomas were arrested, but Bogle could not be found. Bogle was caught by a party of Maroons and brought to Morant Bay for trial. He was hanged on October 24, 1865.

In 1965, a statue of Paul Bogle was erected in front of the Morant Bay courthouse and, in 1969, Paul Bogle was named a National Hero of Jamaica.

Statue of Paul Bogle in front of the Morant Bay Courthouse

ACTIVITY

FILL-IN-THE-BLANKS COMPREHENSION TEST

Read the passage above and the sentences below, then unscramble the words and fill in the blanks with the correct answers.

yotsn — Paul Bogle was born in _______ Gut, St. Thomas.

cadoen — Paul Bogle was a _________ in the Native Baptist Church.

myra — Paul Bogle drilled his followers to form a small ________.

srooman — Paul Bogle was caught by a party of ____________and brought for trial.

atteus — In 1965, a ___________ of Bogle was erected in front of the Morant Bay Courthouse.

laatnion — In 1969, Paul Bogle was named a _________ Hero of Jamaica.

Correct answers: Stony, deacon, army, Maroons, statue, National.

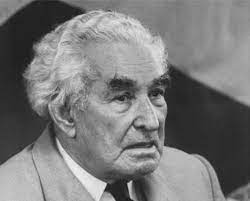

THE LIFE AND WORK OF SIR ALEXANDER BUSTAMANTE, NATIONAL HERO OF JAMAICA

National Hero, the Right Excellent Sir Alexander Bustamante, was born on February 24, 1884 in Blenheim, Hanover. He was from a modest pen-keeping family and was christened William Alexander Clarke. His father, Robert Clarke, was Irish and his mother, Mary Clarke, was a Jamaican of mixed race.

THE LIFE AND WORK OF THE RT. EXCELLENT SAMUEL SHARPE, NATIONAL HERO OF JAMAICA

Samuel Sharpe was born enslaved, but his owner, after whom he was named, took a special liking to him and allowed him to learn to read and write. However, despite his luck, he considered it degrading to be owned by another human being.

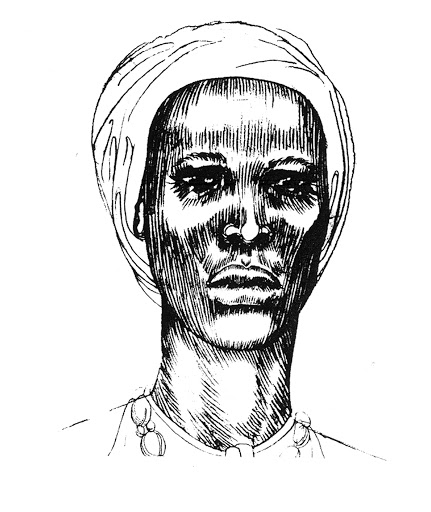

THE LIFE AND WORK OF NATIONAL HEROINE NANNY

The Rt. Excellent Nanny came to Jamaica as an enslaved African along with her five brothers – Cudjoe, Accompong, Johnny, Cuffy and Quao. Scholars believe that Nanny and her brothers were from the Ashanti tribe of West Africa.

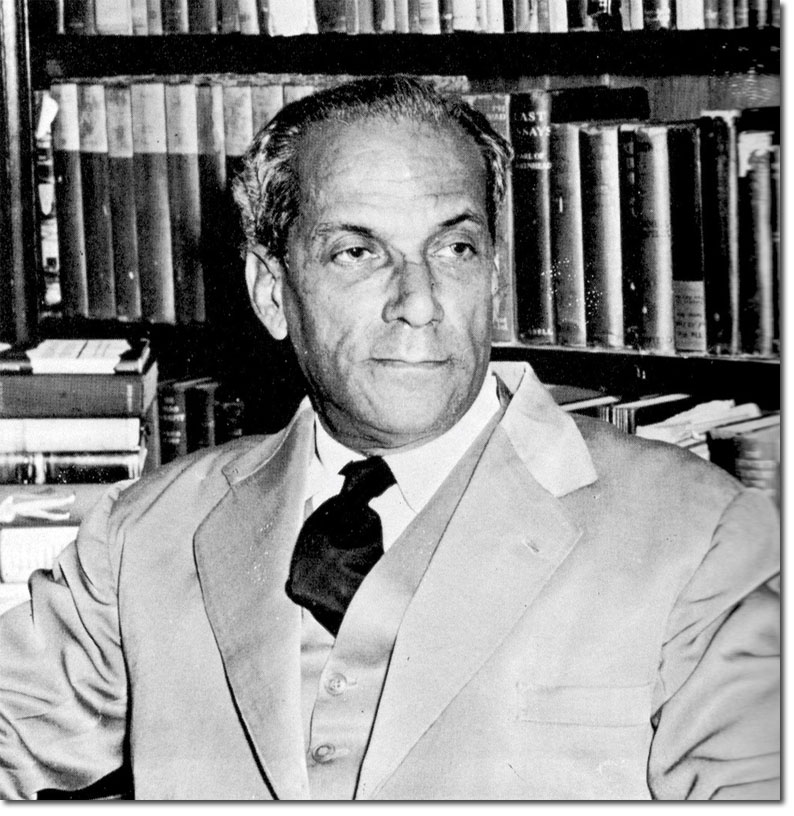

THE LIFE AND WORK OF NORMAN WASHINGTON MANLEY, NATIONAL HERO OF JAMAICA

The Right Excellent Norman Washington Manley M.M., Q.C., B.C.L., LLD (Hon.), National Hero of Jamaica, was born on July 4, 1893 in Roxborough, Manchester. He was the son of Thomas, (a produce dealer), and his wife, Margaret. His father died when he was six years old and the family moved to Belmont, in Guanaboa Vale.